Today, I made a new batch of mead. My last batch turned out okay, but not great. I learned an important lesson and I will share it with you: what I said everyone will tell you about the bitter part of citrus peel having no place in the must, even for a short time, is absolutely true. I can taste the bitterness that is unique to this even though the peel was only in the must for about half an hour. Next time, I will get one of those bartender tools for getting large and decorative strips of citrus zest to get just the good part. The batch is still drinkable, but I'm probably going to use it for meadmosas (like a mimosa, but with mead; try it).

So, I've been pondering over this batch for the last few weeks. My goal, something awesome that could be even more awesome in the winter served warm or even mulled. I got to thinking, and cider is an ancient love of mine, so I set out to make a winter cyser; mead made with apples or cider.

Of course, another love of mine is malt. I love malted milk balls, I love malted milkshakes, and I especially love beer. I've been wanting to use malt for a while and decided to include it in the recipe by replacing half of the sugar I intended to get from honey with malt instead. I'm not really sure if this is the standard proportions of a braggot; mead made with malt; but I just went with what felt right, you know?

I started by getting the malt. I like your standard amber lager as far as beer, so I got amber malt. I intended to use local apple cider, but couldn't find any. At least, not immediately. If this batch works out like I want, I will source some. In the meantime, I got 3 pounds of red delicious apples. Also, I got half the honey I normally would for a gallon batch.

Since I didn't have the cider already pressed from the apples nor did I have a juicer or apple press available, the burden of separating the apples from their delicious cider-blood. While I was boiling the gallon of water for the batch, I cored the apples and cut them into 8 slices which I chopped fairly uniformly and tossed them into the water to keep them from browning. Once they were all done I covered it and let them simmer for a bit to soften the apples. It smelled amazing.

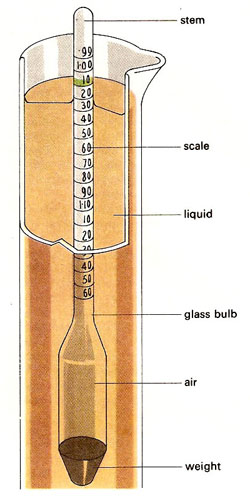

Once the apples were soft, I scooped them out with a spider and tossed them in a blender to pulverize them and added the apple sauce back to the soon-to-be must. I let this cool down enough to get a reading with the hydrometer; 1.004. The apples provided about 0.014 specific gravity, and I was aiming for about a 1.105 to make this batch drier than I have in the past. The remaining desired sugar, another 0.101 increased specific gravity, was to be split between malt and honey; 0.0505 per source.

3 ounces of honey in a gallon of water provides about 0.0075 change in gravity. So:

So, I've been pondering over this batch for the last few weeks. My goal, something awesome that could be even more awesome in the winter served warm or even mulled. I got to thinking, and cider is an ancient love of mine, so I set out to make a winter cyser; mead made with apples or cider.

Of course, another love of mine is malt. I love malted milk balls, I love malted milkshakes, and I especially love beer. I've been wanting to use malt for a while and decided to include it in the recipe by replacing half of the sugar I intended to get from honey with malt instead. I'm not really sure if this is the standard proportions of a braggot; mead made with malt; but I just went with what felt right, you know?

I started by getting the malt. I like your standard amber lager as far as beer, so I got amber malt. I intended to use local apple cider, but couldn't find any. At least, not immediately. If this batch works out like I want, I will source some. In the meantime, I got 3 pounds of red delicious apples. Also, I got half the honey I normally would for a gallon batch.

Since I didn't have the cider already pressed from the apples nor did I have a juicer or apple press available, the burden of separating the apples from their delicious cider-blood. While I was boiling the gallon of water for the batch, I cored the apples and cut them into 8 slices which I chopped fairly uniformly and tossed them into the water to keep them from browning. Once they were all done I covered it and let them simmer for a bit to soften the apples. It smelled amazing.

Once the apples were soft, I scooped them out with a spider and tossed them in a blender to pulverize them and added the apple sauce back to the soon-to-be must. I let this cool down enough to get a reading with the hydrometer; 1.004. The apples provided about 0.014 specific gravity, and I was aiming for about a 1.105 to make this batch drier than I have in the past. The remaining desired sugar, another 0.101 increased specific gravity, was to be split between malt and honey; 0.0505 per source.

3 ounces of honey in a gallon of water provides about 0.0075 change in gravity. So:

- 3*0.0505/0.0075

- gives us 20.2 ounces of honey, give or take.

- 16*0.0505/0.054

- gives us 15.96, or as close to make little difference, the full 16 ounces in a pound of malt.

When it was cooled off enough, I used a new trick I came up with (and after discussion with my friendly homebrew store worker, confirmed that it was a good idea) and pitched in a beer yeast. The beer yeast is specifically bred to process malt sugars where the wine yeast may not be able to handle them. At least, not as well. Once the fermentation stops on the beer yeast, I will siphon it off and pitch in wine yeast to finish fermenting the rest of the way.

I'm super happy with the color, a beautiful dark cider. And the beer yeast is already bubbling away at a bubble every 2 seconds in the airlock. I drank a little bit of the remaining must and it tastes and smells amazing, though of course too sweet.